Blocks and Dyes of Bagru

Read Below for an excerpt from a larger essay

The Dyes

Within Block printing in India, exist 2 types of dyes- the chemical and the natural. And it would seem plain to me which one is to be preferred.

Natural dyes in India are what helped its ancient trade thrive and added the USP- colour fastness- that was eventually killed by industrialising Europe’s advent of chemical dyes.

Natural dyes in India worked due to craftsmen’s knowledge of Mordants- usually salts of metals that allowed fabric fibres to be receptive to dye, salts that allowed the dye to adhere to the fabric, permanently rather than temporarily.

The textile industry has often been criticised for its lack of environmental concern displayed by the unimaginably vast amount of chemicals it spews into water bodies, natural dyes bypass that disadvantage whilst keeping traditions alive.

Whilst some mordants using chromium or tin are environmentally nocuous, most craftsmen stick to the environmentally friendly Alum (Potassium Aluminium Sulphate or Potash).

Red

Red comes from Madder which contains the compound alizarin and is extracted from the roots, Rubia Cordifolia or Rubia Tinctoria. This dyestuff is a stalwart of Indian natural dyers and (unlike Indigo) is an additive dye: indicating that it requires a mordant to bind it to fabric.

Either fresh or dried Manjishtha (Madder Root) is boiled in water along with the mordant: either wood from the Aal (Indian Mulberry Tree) or Potash, then reduced and applied to fabric.

Yellow

Yellwo can be made from Anaar ka chilka (pomegranate peels), Haldi (turmeric) or Kesula ke Phool (flowers of the Bastard Teak).

Yellow is also an additive dye made via boiling turmeric, pomegranate peels, Bastard teak flowers or a combination of the three in water, along with the mordant- Potash, until a thick paste is formed, and this is then applied.

Blue

Indigo is made from Indigo or Indigofera Tinctoria. The making of blue is a significantly tricky process. Indigo leaves have to be fermented in water for a period in order to extract Indican, the blue pigment from the otherwise colourless leaves. The mixture is then boiled and reduced to a jam-like consistency which is then further pressed into cake form.

When dyeing these cakes are put in vats of water along with Sodium Hydrosulphite to deoxidise the mixture.

Removing oxygen is necessary for Indigo dyes as it only adheres to the fabric in oxygen-less conditions. The deoxidised mixture will be green in colour, and when the fabric is removed after immersion in the dye, the green will rapidly turn to blue as it oxidises.

Black or Syahi Begar

Black is made from the fermentation of iron scraps and Gud (Jaggery). The metal and jaggery is fermented in a vessel for up to 21 days depending on atmospheric conditions, the liquid is then poured out, and the remaining paste is strained through muslin before use.

Brown

is made from Babul ki Chaal (branches of the Gum Arabica tree).

Green

Green is made from the addition of turmeric dyes to Indigo dyes.

When overlaid, the two dyes can create deep green shades, however as yellow dyes tend to fade, the final colour upon multiple washes might dry to light teals.

Maroon

Maroon is made from Gehru ( Ochre mud).

Mordants

The role of Mordants is essential to Indian textile’s historical success. Indeed, Indian craftsmen’s knowledge of these metallic salts led to India monopolising coloured and patterned fabrics until the Industrial Revolution.

Mordants, like ferrous acetate ( which is why iron is fermented with Jaggery in black dyes) or Potash, have been used for centuries. Other less eco-friendly mordants like copper sulphate, chrome or tin have also been used but now are increasingly being replaced by Potash or Iron Acetate.

Additional to their role as “fixers”, some Mordants can also change the colours of dyes. Iron makes dyes darker or less saturated, allowing greys and cerulean shades to be made. Chuna” (Calcium Carbonate/Limestone) makes dyes lighter.

In Bagru, Halda (Dried Amla/Indian Goosberry Powder) is also used as a priming agent (rather than being added to the dye) applied as a precoat directly to the fabric.

Resist Media

Resist media is a distinguishing feature of Indian blockprints, and in Bagru, the Daboo variant relies solely on the Daboo paste which is a mixture of Chia ka Atta (tamarind flour), Daboo Kali Mitti (Daboo black mud) and Gud(Jaggery).

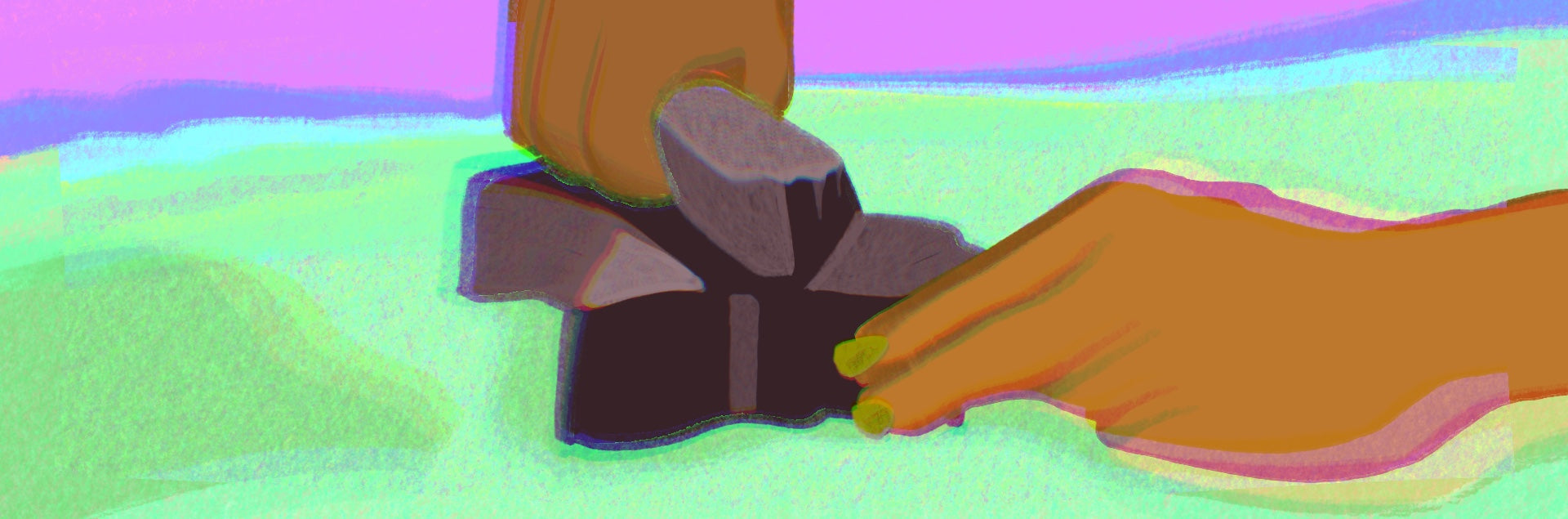

The Blocks

The process of making the printing blocks is a completely different craft altogether, done by different craftsmen across India.<

For printers (chhipas) blocks are akin to a raw material needed to be bought. At the Anokhi Museum of Block Printing, we met a block maker from the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, whom we asked about the block making process.

Blocks are usually made from local hardwoods such as Sheesham(Indian Rosewood) or imported hardwoods such as Burmese teak. Blocks are cut into tapering Gajar (Carrot) shaped pieces and soaked in coconut oil.

The carving of blocks is an incredibly intricate process and uses multiple tools. Patterns are usually made on paper (A reusable template) around a grid; this same grid is then shallowly engraved on the wood. The paper is coated in oil to make it translucent and aligned with the grid on the block after which the process of Tipai takes place.

Tipai is how the pattern’s basic outline is transferred to the wood- small pin-sized holes are hammered into the wood through the paper- this allows the paper to be reused and the pattern engraved.

The process of Tipai is extremely time-consuming taking up to a month for more complex patterns, and as most designs need a multi-block set: one block for the background, one for the motif, individual ones for varying layers of detail and one for a final outline block, the process will only take longer.

After Tipai, a multitude of tools is used to chisel and carve out the pattern, including a handheld bow-drill.

Materials other than wood are also used to make blocks- brass strips are often shaped with a different set of tools and inlaid into wood.

Holes are often made in the body of the block to allow air to escape.

Sometimes Namda wool (which is the waste sheep wool left from the weaving of fabrics forJajam Floor spreads and Dhurries) is used in relatively large blocks, like those used to print the Jajams. This wool waste is soaked in tree gum and pressed into the hollows of blocks allowing for even dye absorption and printing.

In Daboo the mud resist is often daubed on with a rag or brush instead of using blocks to cover larger spaces faster.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.